Big Boy is coming to Texas!

No, not that one.

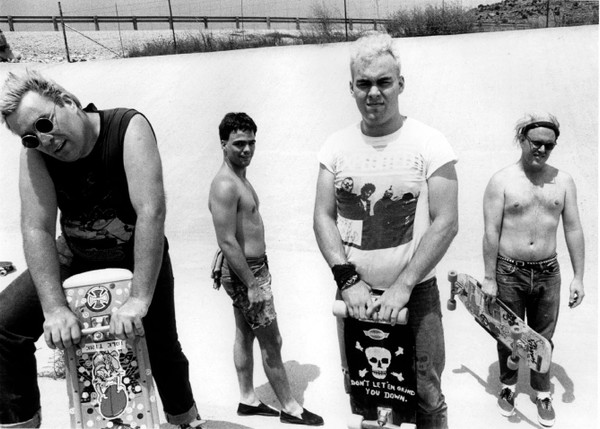

Not them, either. They are (or were) already good Texas boys. But I threw that in because I recently discovered a fun fact about one of the Big Boys, which I will put at the bottom of this post.

This Big Boy is Big Boy 4014, the Union Pacific steam locomotive. It is the second largest steam locomotive ever built, and the largest still in operation.

You may recall that I linked to a couple of videos on Big Boy during the recent unpleasantness.

Here’s the UP schedule for the “Heartland of America Tour”. The tour has already kicked off, but it doesn’t look like Big Boy will reach Texas until September 17th.

It will be in:

- Dallas, September 18th.

- Houston, October 6th.

- Bryan, October 8th.

- Fort Worth, October 10th and 11th.

Check the schedule for more details, and keep in mind that the schedule may change due to mechanical or other issues.

I’m trying to decide if I want to go to Bryan, which is slightly closer, but is “viewing only”, or Houston, which is a little further away, but seems to be more open to the public for touring. If I can pull it together to do one or the other, I’ll post a report here.

That fun Big Boys fact I promised you? Tim Kopra, who played horns with the band, went on to bigger and better things. He became a NASA astronaut. Here’s his NASA biography.

Unusual career trajectory, I think.